| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | -- | 1398 | 2025-05-16 03:57:46 |

Video Upload Options

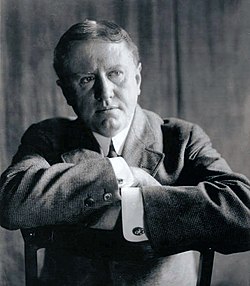

O. Henry (William Sydney Porter, b. September 11, 1862 – d. June 5, 1910) was a celebrated American author best known for his more than 600 short stories characterized by humor, sentimentality, and unexpected endings. Writing during the early 20th century, he became a defining voice in popular fiction, with notable works such as “The Gift of the Magi,” “The Last Leaf,” and “The Cop and the Anthem.” His stories often explored the lives of ordinary people in New York City and beyond.

1. Introduction

William Sydney Porter, better known by his pen name O. Henry, is one of the most celebrated short story writers in American literature. Revered for his ironic twists, engaging urban tales, and sentimental humanity, O. Henry wrote prolifically in the early 20th century, producing over 600 short stories that captivated a growing middle-class readership. His legacy rests not only in the volume and wit of his work but in how he transformed the short story form into a popular, accessible art.

By W.M. Vanderweyde, New York - NYPL Digital Gallery, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9810360

2. Early Life and Background

William Sydney Porter was born on September 11, 1862, in Greensboro, North Carolina, during the American Civil War. His father, Algernon Sidney Porter, was a physician and inventor; his mother, Mary Jane Virginia Swaim Porter, died from tuberculosis when he was only three years old. The young Porter was subsequently raised by his paternal grandmother and aunt, both of whom instilled in him a love for classic literature and storytelling [1].

Though he exhibited an early affinity for language, he did not receive a formal collegiate education. After leaving school at 15, Porter apprenticed as a pharmacist, earning a license at 19. He later moved to Texas in 1882, where he lived for over a decade, holding various jobs, including ranch hand, draftsman, bank teller, and journalist [2].

3. Texas Years and Literary Foundations

It was in Texas that Porter began writing short sketches and columns under pseudonyms. He eventually settled in Austin, where he married Athol Estes in 1887. Their union was plagued by poor health and instability, but Athol played a crucial emotional role in Porter's life and work.

Porter’s time in Austin marked a pivotal phase in his artistic development. He worked at the First National Bank of Austin, where he would later be accused of embezzlement—charges that dramatically affected the course of his life and literary career [3]. During this time, he also published a short-lived humor magazine, The Rolling Stone, which, though unsuccessful commercially, showcased his gift for satirical prose and whimsical observation.

4. Legal Troubles and Imprisonment

In 1896, Porter was indicted for embezzling approximately $854 from the bank. Instead of facing immediate trial, he fled to Honduras, a country then popularized in literature and legend as a haven for American fugitives. His time in Honduras inspired his first book, Cabbages and Kings (1904), a collection of interconnected stories that satirized the political instability of fictional Central American republics. This work also introduced the term “banana republic” into the English lexicon.

Porter returned to the U.S. in 1897 upon learning that his wife was gravely ill. She died shortly afterward, leaving him a single father to their young daughter, Margaret. Porter surrendered to authorities and was sentenced to five years in the Ohio Penitentiary in 1898. He served three years, earning early release for good behavior [2].

It was during his prison term that William Porter began to use the pseudonym “O. Henry”, reportedly to conceal his identity and protect his daughter from disgrace. The true origin of the pen name remains uncertain, though some believe it may have been inspired by a prison guard named Orrin Henry or taken randomly from a newspaper [3].

5. Literary Breakthrough and New York Period

Following his release in 1901, O. Henry moved to New York City, which became the backdrop for many of his most famous stories. His literary output during the first decade of the 20th century was prolific, averaging a story a week at the height of his career.

O. Henry became a regular contributor to McClure’s Magazine, Everybody’s Magazine, and The New York World, which published his weekly stories for over two years. His fiction found a growing audience in an urbanizing America eager for entertaining, digestible literature that reflected everyday experiences and offered escape.

His story collections—The Four Million (1906), The Trimmed Lamp (1907), The Voice of the City (1908), and others—cemented his reputation. He was particularly acclaimed for his keen ear for dialect, observational humor, and mastery of the surprise ending—a signature that became his literary hallmark.

6. Thematic Style and Literary Legacy

O. Henry's stories are often set in cosmopolitan settings, populated by clerks, shopgirls, drifters, and small-time criminals. These characters are marked by moral complexity and situational irony, embodying the dreams and contradictions of early 20th-century American life. His most famous work, “The Gift of the Magi”, captures the poignant absurdity of self-sacrifice and love, telling the story of a young couple who each sells their most prized possession to buy a gift for the other.

Other notable stories include:

-

“The Ransom of Red Chief” – a comedic tale in which two hapless kidnappers are outwitted by their young captive.

-

“The Last Leaf” – a sentimental narrative of hope and sacrifice among struggling artists.

-

“A Retrieved Reformation” – a redemptive story of a reformed safecracker inspired by love and given a second chance.

O. Henry’s stories frequently end with ironic reversals or moral twists that challenge readers’ assumptions. While his style was sometimes criticized as formulaic or sentimental by literary critics, his ability to entertain and engage a broad readership ensured his enduring popularity.

His thematic concerns often included:

-

Urban alienation and community.

-

Social class and economic hardship.

-

Redemption and morality.

-

Romantic idealism.

-

Human folly and compassion.

7. Personal Struggles and Decline

Despite his literary fame, O. Henry struggled personally. He was known to be reclusive and shy, often withdrawing from public life. He also battled alcoholism, which affected his health and productivity in later years. Financial mismanagement and his drinking habits compounded his difficulties.

His relationships were also strained. He remarried briefly in 1907 to his childhood sweetheart, Sarah Lindsey Coleman, but the union was short-lived.

Porter’s final years were marked by declining health. He suffered from cirrhosis of the liver, diabetes, and other complications. His literary output dwindled, and he became increasingly isolated. O. Henry died on June 5, 1910, in New York City, at the age of 47. He was buried in Asheville, North Carolina.

8. Posthumous Recognition and Honors

O. Henry’s work continued to be celebrated after his death. In 1919, the O. Henry Award was established to honor outstanding short stories in American literature. It remains one of the most prestigious awards for short fiction in the English language.

His stories have been adapted into numerous films, radio plays, and television episodes. Hollywood films like O. Henry’s Full House (1952) anthologized several of his stories, bringing his narratives to wider audiences. His style also influenced writers such as Saki (H.H. Munro), Roald Dahl, and Jeffrey Archer, who have employed similar twist endings and moral complexity.

Academically, O. Henry has been the subject of both admiration and critique. While modernist critics often dismissed his work as overly sentimental or gimmicky, more recent scholarship has re-evaluated his contributions to urban realism, narrative economy, and the democratization of American literature [4].

9. Selected Works

9.1. Major Collections

-

Cabbages and Kings (1904)

-

The Four Million (1906)

-

The Trimmed Lamp (1907)

-

Heart of the West (1907)

-

The Voice of the City (1908)

-

Roads of Destiny (1909)

-

Options (1909)

-

Strictly Business (1910)

-

Whirligigs (1910)

9.2. Representative Stories:

-

“The Gift of the Magi”

-

“The Ransom of Red Chief”

-

“A Retrieved Reformation”

-

“The Last Leaf”

-

“The Cop and the Anthem”

-

“Mammon and the Archer”

10. Conclusion

O. Henry's writing captured the complexities, ironies, and humanity of his time. His gift for storytelling lay in his ability to extract humor and warmth from everyday situations, to weave tales with accessible prose, and to leave readers with unexpected yet emotionally resonant conclusions. As a figure of literary Americana, he stands not only as a craftsman of the short story form but as a chronicler of the urban American spirit at the dawn of the 20th century.

In an era that prized efficiency, growth, and novelty, O. Henry offered moments of stillness, humor, and reflection—qualities that have ensured the longevity of his work and relevance of his insight into the human condition.

References

- Current-Garcia, Eugene. O. Henry: A Study of the Short Fiction. Twayne Publishers, 1965.

- Langford, Gerald. Alias O. Henry: A Biography of William Sydney Porter. Macmillan, 1982.

- Smith, C. Alphonso. O. Henry: Biography of William Sydney Porter. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1916. Reprinted 1990.

- Ferguson, Suzanne. "O. Henry and the American Short Story Tradition." Studies in Short Fiction, vol. 43, no. 2, 2006, pp. 135–150.