| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | -- | 1479 | 2025-06-04 04:11:23 |

Video Upload Options

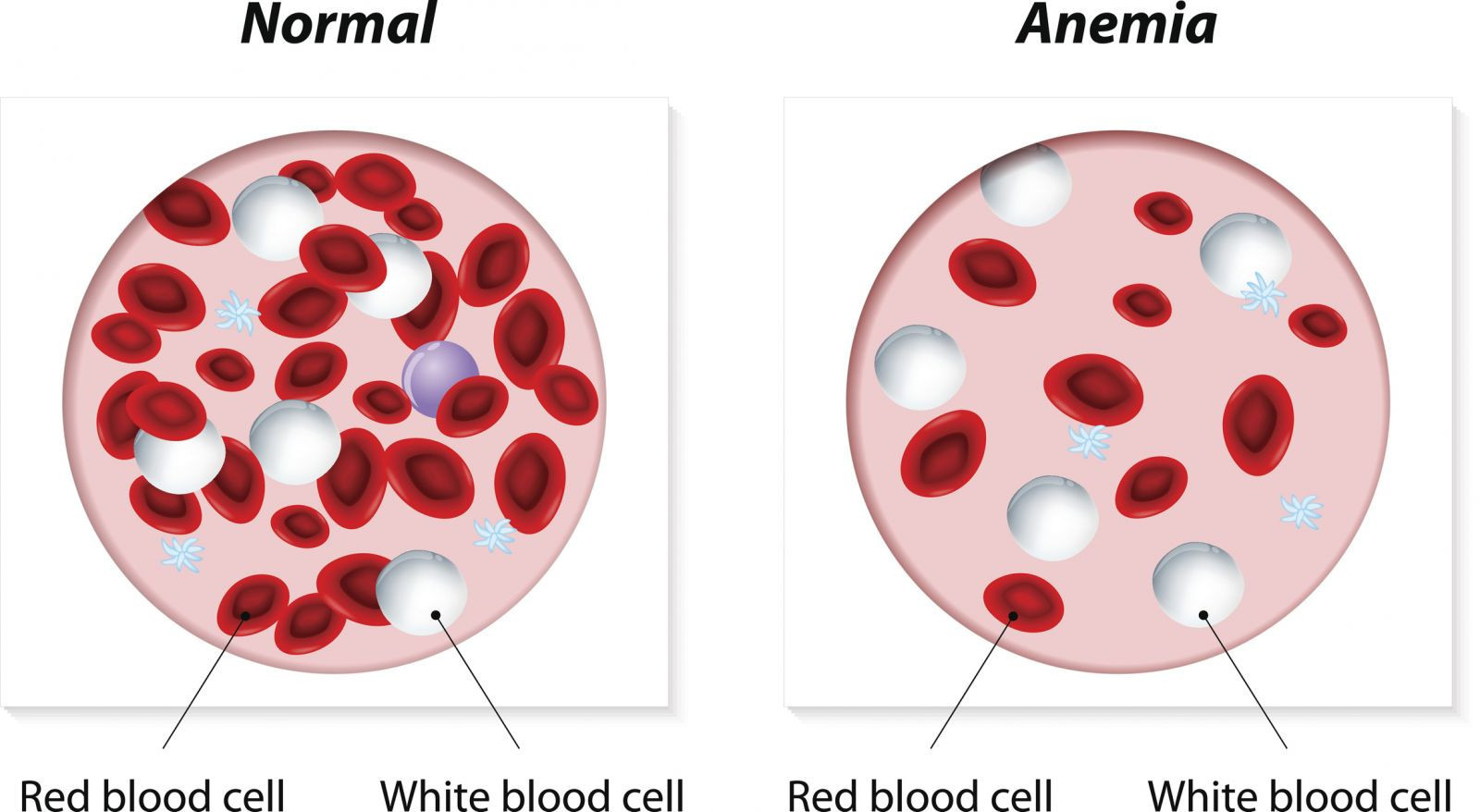

Anemia is a medical condition in which the body does not have enough healthy red blood cells (RBCs) or hemoglobin to carry adequate oxygen to the body's tissues. Hemoglobin is an iron-rich protein in red blood cells that binds oxygen in the lungs and delivers it to the rest of the body.

1. Introduction

Anemia is a medical condition characterized by a decrease in the total number of red blood cells (RBCs), a reduction in hemoglobin concentration, or a diminished hematocrit value, leading to impaired oxygen transport to tissues. This systemic deficiency in oxygen delivery can result in a range of clinical symptoms, from fatigue and weakness to life-threatening cardiovascular complications. Anemia itself is not a singular disease but a clinical sign indicative of various underlying pathological processes. These processes may include nutritional deficiencies, chronic diseases, genetic mutations, or bone marrow disorders [1].

Source: Harvard Health.

2. Epidemiology

Anemia is a prevalent global health issue affecting individuals across all age groups, socioeconomic strata, and geographic regions. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it is estimated that over 1.62 billion individuals globally suffer from anemia, representing approximately 24.8% of the world population [2]. The highest prevalence is observed among preschool-aged children (47.4%), pregnant women (41.8%), and non-pregnant women of reproductive age (30.2%). In many low- and middle-income countries, iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) remains the most significant cause, often exacerbated by parasitic infections, poor dietary intake, and limited access to healthcare. In contrast, in high-income nations, anemia is frequently associated with chronic disease, malignancy, and aging.

3. Classification of Anemia

Anemia is commonly classified based on red blood cell morphology, underlying etiology, and the pathophysiological mechanism. These classifications facilitate accurate diagnosis and targeted therapeutic intervention.

3.1. Morphological Classification

The morphological approach is grounded in the measurement of mean corpuscular volume (MCV), categorizing anemia into:

-

Microcytic anemia (MCV < 80 fL): Characterized by small red blood cells. Common causes include iron deficiency, thalassemia, and sideroblastic anemia.

-

Normocytic anemia (MCV 80–100 fL): Involves red blood cells of normal size but reduced number or hemoglobin content, frequently associated with acute blood loss, anemia of chronic disease, or bone marrow disorders.

-

Macrocytic anemia (MCV > 100 fL): Involves large red blood cells, often due to impaired DNA synthesis. Typical causes include vitamin B12 or folate deficiency and myelodysplastic syndromes.

3.2. Etiological Classification

This method categorizes anemia based on causative factors:

-

Decreased RBC production: Resulting from deficiencies (iron, B12, folate), bone marrow failure (e.g., aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndromes), or chronic disease (e.g., chronic kidney disease).

-

Increased RBC destruction (Hemolysis): Can be inherited (e.g., sickle cell disease, hereditary spherocytosis) or acquired (e.g., autoimmune hemolytic anemia, infections, toxins).

-

Blood loss: Acute hemorrhage (e.g., trauma, surgery) or chronic losses (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding, menorrhagia).

4. Pathophysiology

Red blood cells function primarily to deliver oxygen from the lungs to peripheral tissues and return carbon dioxide for exhalation. Hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying component, is essential for this process. When anemia develops, oxygen delivery becomes inadequate, leading to tissue hypoxia. The body responds through compensatory mechanisms, including increased cardiac output, elevated respiratory rate, and enhanced erythropoietin production by the kidneys to stimulate erythropoiesis in the bone marrow. Chronic anemia may result in left ventricular hypertrophy, angina, or high-output heart failure, particularly in individuals with preexisting cardiovascular disease [3].

5. Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of anemia varies based on its severity, rate of onset, patient age, and comorbidities. Symptoms commonly associated with anemia include:

-

Generalized fatigue and weakness

-

Pallor of the skin and conjunctivae

-

Dyspnea on exertion

-

Dizziness or lightheadedness

-

Tachycardia and palpitations

-

Headache and cognitive difficulties

In severe or rapidly developing anemia, patients may exhibit signs of cardiovascular decompensation, including syncope, angina, or congestive heart failure. Specific types of anemia may also produce unique clinical findings. For instance, vitamin B12 deficiency may lead to glossitis, peripheral neuropathy, and neuropsychiatric disturbances, while hemolytic anemias may present with jaundice, dark urine, and splenomegaly.

6. Diagnostic Evaluation

Accurate diagnosis of anemia requires a combination of clinical assessment and laboratory investigations:

-

Complete blood count (CBC): Provides values for hemoglobin, hematocrit, RBC count, MCV, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and red cell distribution width (RDW).

-

Peripheral blood smear: Assesses RBC morphology, identifying anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, or inclusion bodies.

-

Reticulocyte count: Reflects bone marrow response; increased in hemolysis or blood loss, decreased in marrow suppression.

-

Iron studies: Includes serum ferritin, serum iron, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and transferrin saturation.

-

Vitamin levels: Serum B12 and folate levels help detect macrocytic anemias.

-

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), haptoglobin, bilirubin: Useful in evaluating hemolysis.

-

Bone marrow biopsy: May be necessary in cases of unexplained anemia or suspected marrow pathology.

Additional tests may include hemoglobin electrophoresis (for thalassemia or sickle cell disease), Coombs test (for autoimmune hemolytic anemia), and genetic testing for inherited anemias.

7. Types of Anemia

7.1. Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA)

This is the most common form of anemia globally. It results from inadequate iron intake, increased iron requirements (e.g., pregnancy), or chronic blood loss (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding). Laboratory findings include low hemoglobin, low serum ferritin, high TIBC, and microcytic, hypochromic red cells.

7.2. Anemia of Chronic Disease (ACD)

Also known as anemia of inflammation, ACD is common in patients with chronic infections, autoimmune disorders, malignancies, or chronic kidney disease. It is mediated by inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6) that impair iron utilization and reduce erythropoietin response.

7.3. Megaloblastic Anemia

This macrocytic anemia arises from impaired DNA synthesis due to vitamin B12 or folate deficiency. Neurological symptoms are more pronounced in B12 deficiency. Causes include malabsorption (e.g., pernicious anemia), poor dietary intake, or medications (e.g., methotrexate).

7.4. Hemolytic Anemia

Characterized by premature destruction of RBCs, it can be intrinsic (e.g., hereditary spherocytosis, G6PD deficiency) or extrinsic (e.g., autoimmune hemolytic anemia, infections). Hallmark features include elevated LDH, indirect hyperbilirubinemia, low haptoglobin, and increased reticulocyte count.

7.5. Aplastic Anemia

A rare condition marked by pancytopenia and hypocellular bone marrow. Causes include idiopathic factors, drug exposure, viral infections (e.g., hepatitis), and autoimmune destruction of hematopoietic stem cells.

7.6. Sickle Cell Disease and Thalassemia

These are inherited hemoglobinopathies. Sickle cell disease results from a point mutation in the β-globin gene, leading to vaso-occlusion and chronic hemolysis. Thalassemias are caused by decreased or absent synthesis of α- or β-globin chains, resulting in ineffective erythropoiesis.

8. Treatment and Management

The treatment of anemia is guided by the underlying etiology:

-

Iron deficiency: Oral ferrous sulfate is first-line; intravenous iron is reserved for severe deficiency or intolerance. Identification and correction of the source of bleeding are essential.

-

Vitamin B12/Folate deficiency: Treated with oral or intramuscular cobalamin and oral folic acid. Lifelong supplementation may be required in cases of pernicious anemia.

-

Anemia of chronic disease: Management focuses on the primary disease. In cases of chronic kidney disease, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) and intravenous iron are commonly used.

-

Hemolytic anemia: Autoimmune forms are treated with corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, or splenectomy. Supportive care includes transfusions and folate supplementation.

-

Aplastic anemia: Options include immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., antithymocyte globulin, cyclosporine) or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in eligible patients.

-

Hemoglobinopathies: Sickle cell disease is managed with hydroxyurea, pain control, transfusions, and potentially curative gene therapy. Thalassemia major may require regular transfusions and iron chelation.

9. Prognosis and Outcomes

The prognosis of anemia depends on its type, severity, and underlying cause. Nutritional anemias often respond well to treatment, whereas anemias due to bone marrow failure or malignancies carry a graver prognosis. Unmanaged anemia, especially in vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, infants, and the elderly, can result in serious complications including:

-

Cardiovascular strain and heart failure

-

Impaired cognitive and motor development in children

-

Increased maternal and perinatal mortality

-

Reduced quality of life and functional capacity

-

Increased postoperative morbidity and mortality

10. Public Health Implications

Anemia remains a significant barrier to global health and economic development. Iron deficiency impairs physical performance, cognitive development, and immune function, leading to increased morbidity. Programs aimed at food fortification, deworming, maternal health, and access to prenatal care have proven effective in reducing anemia prevalence. The WHO's Global Nutrition Target aims to reduce anemia in women of reproductive age by 50% by 2025.

11. Recent Advances and Future Directions

Contemporary research has enhanced understanding of iron regulation, particularly the role of hepcidin, a liver-derived hormone that negatively regulates iron absorption and release. New therapies, such as hepcidin antagonists and HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors (e.g., roxadustat), show promise in treating anemia of chronic kidney disease. Advances in molecular biology and gene therapy offer potential curative approaches for inherited anemias like sickle cell disease and thalassemia.

Moreover, the integration of multi-omics approaches (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) is expected to refine anemia diagnostics and enable personalized medicine. Point-of-care testing, especially in low-resource settings, is crucial for early detection and management.

12. Conclusion

Anemia is a complex, multifactorial condition with wide-reaching implications for individual and public health. A comprehensive understanding of its pathophysiology, etiology, and management is essential for clinicians, researchers, and policy-makers. Continued efforts in prevention, early diagnosis, and innovative treatment strategies are critical to mitigate the global burden of anemia.

References

- Camaschella, C. (2015). Iron-deficiency anemia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(19), 1832–1843. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1401038

- World Health Organization. (2008). Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005: WHO global database on anaemia. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241596657

- Weiss, G., & Goodnough, L. T. (2005). Anemia of chronic disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(10), 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra041809