| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | -- | 1300 | 2025-06-12 04:20:47 |

Video Upload Options

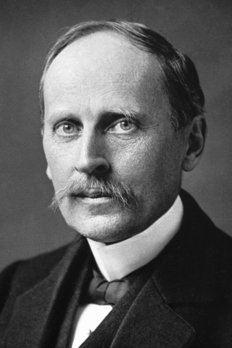

Romain Rolland (1866–1944) was a French novelist, dramatist, essayist, musicologist, and pacifist, recognized for his literary and philosophical contributions that championed humanism, intellectual freedom, and social justice. A Nobel Laureate in Literature (1915), Rolland is best known for his ten-volume novel Jean-Christophe, his biographies of Beethoven and Michelangelo, and his outspoken opposition to war and fascism.

1. Early Life and Education

Born on January 29, 1866, in Clamecy, Nièvre, France, Romain Rolland grew up in a cultivated bourgeois household that valued literature, music, and historical awareness. From an early age, Rolland demonstrated an exceptional intellectual capacity, and his parents encouraged his academic ambitions. He completed his secondary education at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris, where he developed a keen interest in philosophy, literature, and history.

Source: Nobel Prize

In 1886, Rolland enrolled at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure, one of France’s top institutions for training intellectual elites. There, he studied under the guidance of historians such as Gabriel Monod, who exposed him to rigorous historical methods and the importance of moral inquiry in scholarship. After earning his agrégation in history, Rolland spent two formative years in Italy (1889–1891) conducting research on Renaissance art and music. His time in Rome, Florence, and Naples significantly shaped his artistic sensibilities and deepened his commitment to a humanistic vision grounded in both classical and modern culture [1]. His early immersion in German classical culture and his admiration for the intellectual achievements of Goethe, Beethoven, and Wagner would later form the backbone of his literary worldview [2].

2. Academic and Artistic Career

Upon returning to France, Rolland began his academic career at the École Normale Supérieure and later took a position at the Sorbonne, where he taught art history and the history of music. He played a pioneering role in establishing musicology as a serious academic discipline in France, and his lectures often bridged artistic critique with philosophical and historical insight. Rolland's scholarly output during this period included essays and monographs on the ethical and spiritual dimensions of classical music and Renaissance art.

He also began exploring dramatic literature, inspired by classical forms and social themes. His early plays, such as Aërt (1898), Les Loups (1898), and Danton (1900), reveal his fascination with ethical conflict, revolutionary fervor, and the hero’s moral responsibility. These works reflect Rolland’s belief that drama should not merely entertain but also elevate public consciousness and engage with contemporary social dilemmas. In this way, Rolland extended the legacy of writers such as Victor Hugo and Friedrich Schiller [3].

His biographical works were equally influential, blending rigorous historical research with psychological and spiritual insight. Beethoven the Creator (1903), Michelangelo (1907), and Haendel (1910) offered more than traditional biographies—they were, in Rolland’s hands, moral treatises that interpreted the artist’s life as a testament to human greatness and resilience. He celebrated his subjects not merely for their achievements but for their ethical courage in the face of adversity. These works underscored Rolland’s conviction that the true artist must serve as a spiritual guide, resisting mediocrity and moral compromise [2][4][5].

3. Jean-Christophe and the Nobel Prize

Rolland’s greatest literary achievement, Jean-Christophe, was serialized from 1904 to 1912 and later compiled into ten volumes. It chronicles the life and artistic struggles of Jean-Christophe Krafft, a fictional German composer loosely inspired by Beethoven. Spanning his childhood, artistic maturation, disillusionment, and ultimate spiritual redemption, the novel represents a comprehensive vision of the artist as a moral exemplar in a turbulent society [1].

Structured as a Bildungsroman, the novel also serves as a philosophical and cultural treatise on the function of art in modern life. Rolland employs musical metaphors, psychological depth, and panoramic social commentary to depict Europe at a crossroads. He contrasts German and French cultures, critiques nationalism and materialism, and extols the human spirit's capacity for transcendence through suffering and beauty.

The novel’s length, complexity, and idealism made it a landmark in European literature. Its universalist themes were especially resonant during the tense years preceding World War I. In awarding Rolland the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1915, the Swedish Academy recognized the “lofty idealism” of his work and its call for cultural reconciliation and moral awakening [2][4]. The Nobel Prize helped secure Rolland’s international reputation and drew attention to his pacifist philosophy during one of Europe's darkest periods.

4. Political Activism and Pacifism

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a decisive turning point in Rolland’s intellectual journey. While many French intellectuals supported the war effort, Rolland adopted an uncompromising pacifist stance. He published a series of essays under the title Au-dessus de la mêlée (Above the Battle), in which he condemned the nationalistic fervor consuming Europe and called upon writers, scholars, and artists to remain faithful to universal human values [6].

Rolland’s refusal to take sides alienated him from many of his French contemporaries, who accused him of betrayal. Yet he remained steadfast, asserting that true intellectual integrity required moral courage in the face of collective hysteria. From his self-imposed exile in Switzerland, Rolland continued to write essays, letters, and journals that advocated for peace, dialogue, and international solidarity.

Rolland corresponded with leading figures of the global peace movement, including Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Albert Einstein. His admiration for Gandhi was particularly deep, and he published Mahatma Gandhi: The Man Who Became One with the Universal Being in 1924, one of the first major European studies of Gandhi’s thought and work [7][8]. These engagements reflected Rolland’s belief in nonviolent resistance, ethical politics, and the role of the intellectual as a conscience of humanity.

He also supported social reforms and anti-imperialist movements, aligning with various progressive causes throughout the 1920s and 1930s. While he sympathized with some aims of the Soviet experiment, he remained critical of authoritarianism and resisted ideological dogmatism. He maintained an independent voice and viewed socialism not as a rigid system but as an evolving ethical commitment to justice and human dignity [3].

5. Later Works and Intellectual Legacy

In his later years, Rolland continued to write fiction, biographies, and philosophical essays. His novel Clérambault (1920) revisited the themes of pacifism, conscience, and individual moral choice, portraying a French intellectual who struggles with patriotic conformity during wartime. Other works, such as Péguy (1916), Vie de Ramakrishna (1929), and Vie de Vivekananda (1930), demonstrated Rolland’s interest in spiritual traditions beyond the West and his search for global ethical frameworks.

Despite declining health, Rolland remained intellectually active into the 1940s. He died on December 30, 1944, just months after the liberation of Paris. His death marked the end of a career that spanned some of the most turbulent periods in modern history. Throughout his life, he consistently opposed tyranny, militarism, and intellectual complacency, believing that culture and conscience must guide social transformation.

Rolland’s legacy continues to inspire scholars, artists, and peace activists worldwide. His synthesis of literature, ethics, and political engagement set a precedent for the writer as public intellectual. He demonstrated that the artist’s role extends beyond aesthetic creation to moral leadership and civic responsibility [3][5].

6. Influence on 20th Century Thought

Rolland’s influence reached far beyond the literary world. In the interwar years, he was an early and vocal critic of fascism, totalitarianism, and colonial oppression. His insistence on humanist values helped shape the development of the intellectual left in Europe, influencing figures such as André Gide, Stefan Zweig, and E.M. Forster. His writings on music and art paved the way for interdisciplinary studies, blending aesthetic appreciation with social analysis.

Moreover, Rolland’s correspondence with Gandhi and Einstein placed him at the center of international debates on peace, civil resistance, and the future of civilization. He foresaw the dangers of ideological extremism and believed that cultural cooperation and mutual understanding were essential to world peace. Today, his work remains a powerful testament to the capacity of literature to shape ethical discourse and inspire global solidarity [7][8][9].

References

- Rolland, R. (1928–1945). Beethoven: Les grandes époques créatrices [Beethoven: The Creative Epochs]. Paris: Albin Michel.

- Curtis, M. (1959). Three Against the Third Republic: Sorel, Barrès, and Maurras. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Dargan, E. P. (1933). The Life and Writings of Romain Rolland. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Rolland, R. (1915). Au-dessus de la mêlée [Above the Battle]. Paris: Éditions de l’Humanité.

- Molnár, M. (2001). A concise history of Hungary. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rolland, R. (1904–1912). Jean-Christophe. Paris: Ollendorff.

- Rolland, R., & Gandhi, M. (1976). Romain Rolland and Gandhi Correspondence (H. H. Anniah Gowda, Ed.). New Delhi, India: Publications Division.

- Tagore, R. (1967). Letters to Romain Rolland. In Rabindranath Tagore: Letters. Calcutta, India: Visva-Bharati.

- Einstein, A. (1954). Ideas and opinions (S. Bargmann, Trans.). New York, NY: Crown.