| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | -- | 1774 | 2025-06-09 08:18:35 |

Video Upload Options

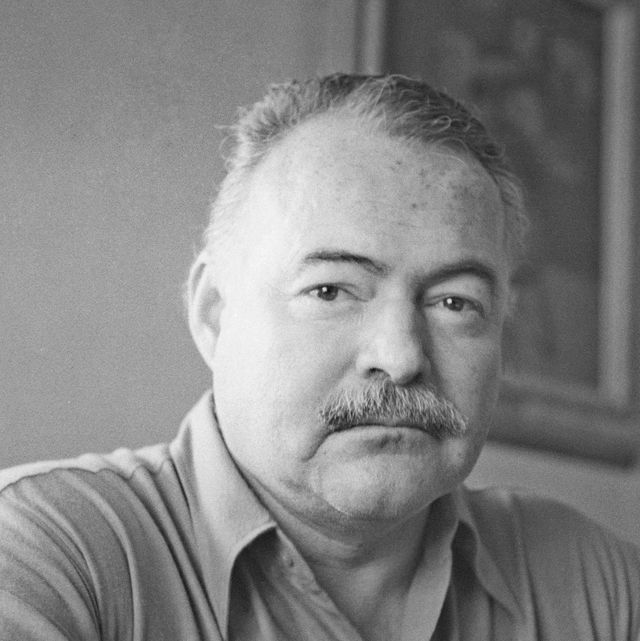

Ernest Miller Hemingway was a Nobel Prize-winning American novelist, short story writer, and journalist whose understated literary style and adventurous life made him one of the most influential writers of the 20th century. Known for works such as The Old Man and the Sea, A Farewell to Arms, and For Whom the Bell Tolls, Hemingway's prose shaped modern fiction and left a lasting imprint on literature, war reporting, and popular culture.

I. Early Life and Education

Ernest Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, to Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, a physician, and Grace Hall Hemingway, a musician. The Hemingway household was conventional and prosperous, emphasizing religion, education, and moral discipline. Hemingway spent his early summers at the family's cabin in northern Michigan, experiences that would later form the basis for many of his early stories, such as those in In Our Time (1925).

Source: Biography

Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School, where he wrote for the school newspaper and yearbook. He did not attend college but began his career in journalism shortly after graduating. In 1917, he took a position as a cub reporter for The Kansas City Star, whose style guide—favoring short sentences and vigorous English—would later influence Hemingway's literary style [1][2][3][4][5].

2. World War I and the Beginnings of Fiction

Hemingway’s early experiences in World War I profoundly influenced both his personal life and literary career. At the age of 18, he volunteered as an ambulance driver for the American Red Cross in Italy. During his service, Hemingway was wounded by mortar fire in the summer of 1918 and spent several months recovering in Milan. The experience left him with permanent physical injuries, but more importantly, it instilled a sense of disillusionment about war, a theme that would become central in many of his works.

Hemingway's physical wounds were not the only scars from the war. His emotional and psychological injuries were more profound. These experiences would shape his writing style and thematic preoccupations. In A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway revisits the subject of war and its dehumanizing effects, particularly focusing on the futility of war and its ability to shatter the human psyche. The novel’s protagonist, Lieutenant Frederic Henry, a fictionalized version of Hemingway himself, is a wounded soldier who becomes entangled in a romantic relationship amid the horrors of war. The novel encapsulates Hemingway’s personal belief in the randomness and horror of war, revealing the devastating impact it has on individuals.

Hemingway’s first short stories, many of which are compiled in In Our Time (1925), reveal his efforts to work through the emotional complexity of his wartime experiences. These stories introduce Nick Adams, Hemingway’s semi-autobiographical protagonist, who returns from the war to try to make sense of his trauma. This collection introduces readers to Hemingway’s minimalist style, where much of the narrative meaning is conveyed in subtext and silence, in line with the so-called "Iceberg Theory." Through these early stories, Hemingway began to hone his distinctive voice: sparse, direct, and emotionally restrained.

In the years following his return to the United States, Hemingway began to write more seriously, using his war experience as a foundation for his exploration of loss, trauma, and the search for meaning in a fractured world. His period as a war correspondent in the Spanish Civil War further shaped his understanding of conflict and its impact on individuals and societies, reinforcing themes of ideological division, sacrifice, and moral conflict in his later work.

3. The Paris Years and Literary Breakthrough

The 1920s marked a crucial period in Hemingway’s development as a writer. In 1921, Hemingway married Hadley Richardson, and the couple moved to Paris, where he would begin to shape his literary career in earnest. The Hemingways were part of a burgeoning expatriate community that included writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein. These figures, who collectively came to be known as the "Lost Generation," represented the disillusionment of the post-World War I era, a generation whose idealistic values were shattered by the brutality of the war.

During this period, Hemingway’s writing began to evolve, influenced by his interactions with these writers and his experiences in Europe. He befriended the renowned poet Ezra Pound, who encouraged Hemingway to write with greater precision and economy, further refining his minimalist style. At the same time, Gertrude Stein, a prominent figure in the Parisian literary scene, mentored him, providing him with both practical advice and philosophical insights into the nature of modern writing. The presence of these literary giants helped Hemingway refine his understanding of narrative form, particularly in the use of subtext and symbolism.

Hemingway’s literary breakthrough came in 1926 with the publication of The Sun Also Rises, which captured the postwar malaise and sense of aimlessness that characterized the Lost Generation. The novel’s protagonist, Jake Barnes, a war veteran, embodies the emotional detachment and physical emasculation that was central to Hemingway’s exploration of masculinity. The novel’s portrayal of expatriates in Paris and Spain, as well as its deep engagement with themes of disillusionment and the search for meaning in a world without clear moral guidance, resonated deeply with contemporary readers and critics.

While The Sun Also Rises was a critical success, it was Hemingway’s second novel, A Farewell to Arms (1929), that solidified his reputation as one of the foremost American writers of his time. Drawing on his own wartime experiences, the novel explores the complex dynamics of love and loss amidst the chaos of World War I. The relationship between Lieutenant Frederic Henry and Catherine Barkley serves as a symbol of love’s fragility, providing a counterpoint to the brutality of war. A Farewell to Arms was widely praised for its simplicity, emotional depth, and realistic portrayal of war. It also marked a significant turning point in Hemingway’s career, as he had now fully embraced his distinctive style and voice.

4. Mid-Career: Spain, Africa, and War Reporting

The 1930s were a period of both personal and professional growth for Hemingway. Following the success of A Farewell to Arms, he traveled extensively, particularly to Spain and Africa, where his experiences would provide inspiration for some of his most iconic works.

In Spain, Hemingway’s passion for bullfighting led him to write Death in the Afternoon (1932), a nonfiction work that examines the cultural and ritualistic aspects of bullfighting. The book reveals Hemingway’s fascination with the intersection of life and death, an enduring theme in his writing. The bullfighter’s stoic acceptance of mortality became a metaphor for Hemingway’s own philosophy of life, which was shaped by his encounters with war, loss, and personal suffering. In his portrayal of bullfighting, Hemingway celebrated the idea of honor in the face of certain death, drawing parallels to the lives of his fictional heroes, who often face death in a similarly courageous and resigned manner.

Hemingway’s interest in Africa also led to the publication of Green Hills of Africa (1935), a nonfiction account of his safari in East Africa. The book blends elements of memoir, adventure narrative, and philosophical reflection, providing insights into Hemingway’s attitude toward nature, masculinity, and human endurance. The safari, however, is also a metaphor for Hemingway’s search for a deeper connection with life—an attempt to reclaim something primal and pure in the face of the modern world’s complexities.

Hemingway’s personal life during this period was equally turbulent. His marriage to Hadley Richardson ended in 1927, and in the years that followed, he married Pauline Pfeiffer, a journalist who had worked with him in Paris. Their marriage brought both personal and professional success, but Hemingway’s relationship with Pauline would be overshadowed by the strain of his infidelities and his increasing obsession with writing. The 1930s also saw the rise of fascism in Europe, and Hemingway, ever the idealist, aligned himself with the Republican cause during the Spanish Civil War, which provided the material for his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). Set during the conflict, the novel follows Robert Jordan, an American dynamiter who joins the resistance against Franco’s fascist forces. The novel’s themes of sacrifice, loyalty, and the nature of ideological conflict reflect Hemingway’s personal beliefs and the complexity of political struggle.

For Whom the Bell Tolls is regarded as one of Hemingway’s finest works. It continues the exploration of death, heroism, and the personal cost of war, but it also reflects Hemingway’s deepening engagement with the philosophical and emotional dimensions of the human experience. The novel’s focus on the internal lives of its characters, particularly Robert Jordan, marked a departure from Hemingway’s earlier, more action-driven narratives, highlighting the depth of his literary ambition and mastery of character.

5. Later Life and Literary Recognition

Hemingway's literary output slowed during World War II, though he served as a correspondent and participated in the D-Day landings and the liberation of Paris. His post-war period included his Pulitzer Prize win for The Old Man and the Sea (1953), a novella about an aging Cuban fisherman's battle with a giant marlin. The work earned Hemingway the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954 "for his mastery of the art of narrative and the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style."

He continued to write but struggled with health issues, depression, and the effects of multiple plane crashes in Africa. In 1961, suffering from deteriorating mental health, Hemingway died by suicide in Ketchum, Idaho.

6. Style and Literary Impact

Hemingway's prose is distinguished by its brevity, clarity, and emotional restraint. His style has influenced generations of writers, including Raymond Carver, Joan Didion, and Cormac McCarthy. The "Hemingway Code Hero"—stoic, courageous, and honorable in the face of inevitable defeat—became a key figure in literary studies.

His approach to dialogue, omission, and understatement revolutionized modern fiction. Critics and scholars continue to debate the gender politics, thematic undercurrents, and autobiographical elements of his work, which remains a subject of rich critical inquiry.

7. Legacy

Ernest Hemingway's legacy endures through his extensive body of work, critical acclaim, and the mythos of his personal life. He has been immortalized in museums, literary societies, and annual festivals, including the Hemingway Days Festival in Key West. His home in Cuba, Finca Vigía, is preserved as a museum, and numerous biographies have examined his complex persona.

Posthumously published works such as A Moveable Feast (1964), Islands in the Stream (1970), and The Garden of Eden (1986) have further contributed to his mystique. Hemingway's writing continues to be taught, studied, and revered around the world as a benchmark of modern literary excellence.

References

- Baker, Carlos. Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Scribner, 1969.

- Meyers, Jeffrey. Hemingway: A Biography. Rev. ed. New York: Harper Perennial, 1999.

- Oliver, Charles M. Ernest Hemingway A to Z: The Essential Reference to the Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1999.

- Reynolds, Michael S. Hemingway: The Paris Years. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989.

- Young, Philip. Ernest Hemingway: A Reconsideration. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1966.